The demonstration of learning is the most critical ingredient in the portfolio. You can demonstrate learning through competency statements organized in point form sentences, paragraphs/essays, or columns. Reflection is a critical component of any academic portfolio and can be documented in several ways including chronological histories, personal and professional learning narratives, and autobiographies.

Chronological histories:

This will list all the major experiences of your life so far and should be written first as it will form the basis of all other narratives.

Personal and Professional Learning Narratives:

Often short and scattered throughout a portfolio, these are written as a reflection on a particular piece of evidence to help the reader understand the importance of that piece of evidence.

Additionally, longer narratives can be written at various points of learning (for example, at the beginning, midpoint, and end of a project) which reflect stages of learning similar to a diary.

Autobiographies:

By far the most ambitious narrative, an autobiography is an important part of a portfolio as it ties together the chronological history and the personal/professional learning narratives.

Writing a Chronological History

You can begin the list when you left high school or went out on your own, and continue to the present. Any experience may qualify, but if you have difficulty deciding think of those lasting at least a month.

Questions to ask:

- Where did the experience take place?

- What was the length of the experience?

- What were your duties and responsibilities?

- What did you learn from the experience?

Life experiences to consider:

Employment, volunteer work, education where you received a grade or a certificate, training not resulting in a grade or certificate, self taught activities, licenses and awards, travel, hobbies and any other activities you believe may be relevant.

How to get help creating your chronological record:

- Talk to friends, family and coworkers

- Look at photo albums

Writing Personal and Professional Learning Narratives

If you are creating an academic portfolio your learning narrative may develop from shorter learning statements. Regardless of the purpose of the portfolio, you should know your audience and the narrative should add to or otherwise address the evidence within your portfolio.

Writing an Autobiography

The following has been adapted and is used with permission from Athabasca University: 2007 "How to Write an Autobiographical Essay/Personal Narrative."

A short summary of your life story, two to four pages, begins your portfolio. It tells the assessor how you got to be who you are now (attitudes and behaviour), what things you did to gain what you know now (knowledge), and what you can do (skills). It is important for the summary to show how you and your abilities are connected to the kind of work you are doing now and what work you hope to do in the future.

There are a number of steps you can follow to help you do this:

1. Drawing a lifeline.

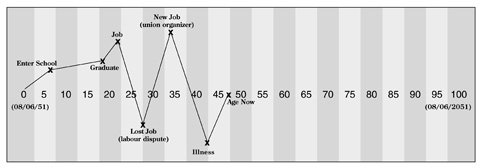

A lifeline (for the purposes of this website, this is equivalent to your chronological history as noted above) is a line drawing that visually shows the important personal and work events, especially voluntary activities, that have happened in your life; for example, you will mark events on the line like your birth, your school entrance, your high school graduation, your first job and any other important highlights (either personal or work related; either large or small) that happened during your life up to the present time that influenced your present learning with respect to your degree program.

How is drawing a lifeline useful to me

A lifeline drawing helps you remember important events in your life so you can write your life story; it is for your personal reference only. It is not put in the portfolio.

How do I draw a lifeline?

2. The importance of marking personal events.

Judge and mark the important (“critical’) events that happened in your life in this way:

If a positive event happened to you, mark your “X” ABOVE the appropriate year on the lifeline and ABOVE the line to a height that tells you how important it was to you; marking the “X” very HIGH above the line means the event was very significant to you; marking the “X” above the line, but CLOSER to the line, means the event was not very significant to you. Apply the converse strategy to any negative events.

3. To begin this process, think about your life as having three stages: the past, the present, and the future.

The following offers detailed instructions on how to revisit your past in order to reflect on your learning – past, present, and future.

Looking into the past

- Think back and identify events in your past that influenced who you are now: what you believe, what is important to you, what you like or dislike.

- These may be from your personal life, or from your physical, spiritual, emotional, or intellectual life; what acquired skills and preferences (those that you were born with or emerged early in life) surfaced in your early work experiences? e.g., what did you learn about yourself from, for example: summers spent with grandparents; a school award; marriages, divorces; births, deaths of family members; recognition for special achievements in sports; a personal best that others might not know about; once these are identified, mark your significant events on the life line with an “X” at the age you were then.

- Make a separate list of your childhood preferences, talents, and patterns of behaviour that contribute to your current activities now; think of the usual milestones that mark the first 20 years of life; what did you learn about yourself in the way you approached, for example, learning to ride a bike; did you struggle to keep at it until you could do it, in spite of scraped knees; did you fall down and then ask the adults in your life to help you until you learned from this group accomplishment.

To help organize your thinking about the past, break it into time segments, such as: AGE 0 – 5, AGE 5 – 10, AGE 10 – 15, AGE 16 – 20, AGE 20 – 30, AGE 30 – 40, and AGE 40 on.

Looking ahead to the Future

- It is hard to know where you are going if you do not have a picture of what you want.

- Think about the life stages you anticipate in the next ten years (e.g., moving; new career; different professional activities; education; retirement)?

- Think of some goals you have and the age by which you want to attain them.

- Mark them with an “X” on your lifeline (e.g., write a book; increase financial security; live near the mountains); remember you aren’t making commitments here, just outlining possibilities.

- Write down any insights you have doing this exercise (e.g., I need time for: union social justice activities; writing; building savings; finding a dream home near the mountains; attaining a university credential.

Summarizing

Use your list of talents and patterns of behaviour to begin writing your autobiographical essay. Keep it brief, but explain how you became the kind of person you are now (attitudes and behaviour). Describe your interests and how these influenced you to learn the skills you have today (knowledge and skills). How did you decide to enter the kind of work you do now? Where do you want to go from here?